A Child’s Christmas in Connecticut

by Jack T. Scully

Christmas times were cold and white as the North Pole when I was a child growing up in Greenwich—all those years ago. Like an unwelcome houseguest, winter came early and left late. The Mianus River, near our house, froze by Pearl Harbor Day, and within a week, daredevils were blasting hockey pucks across the glassy ice.

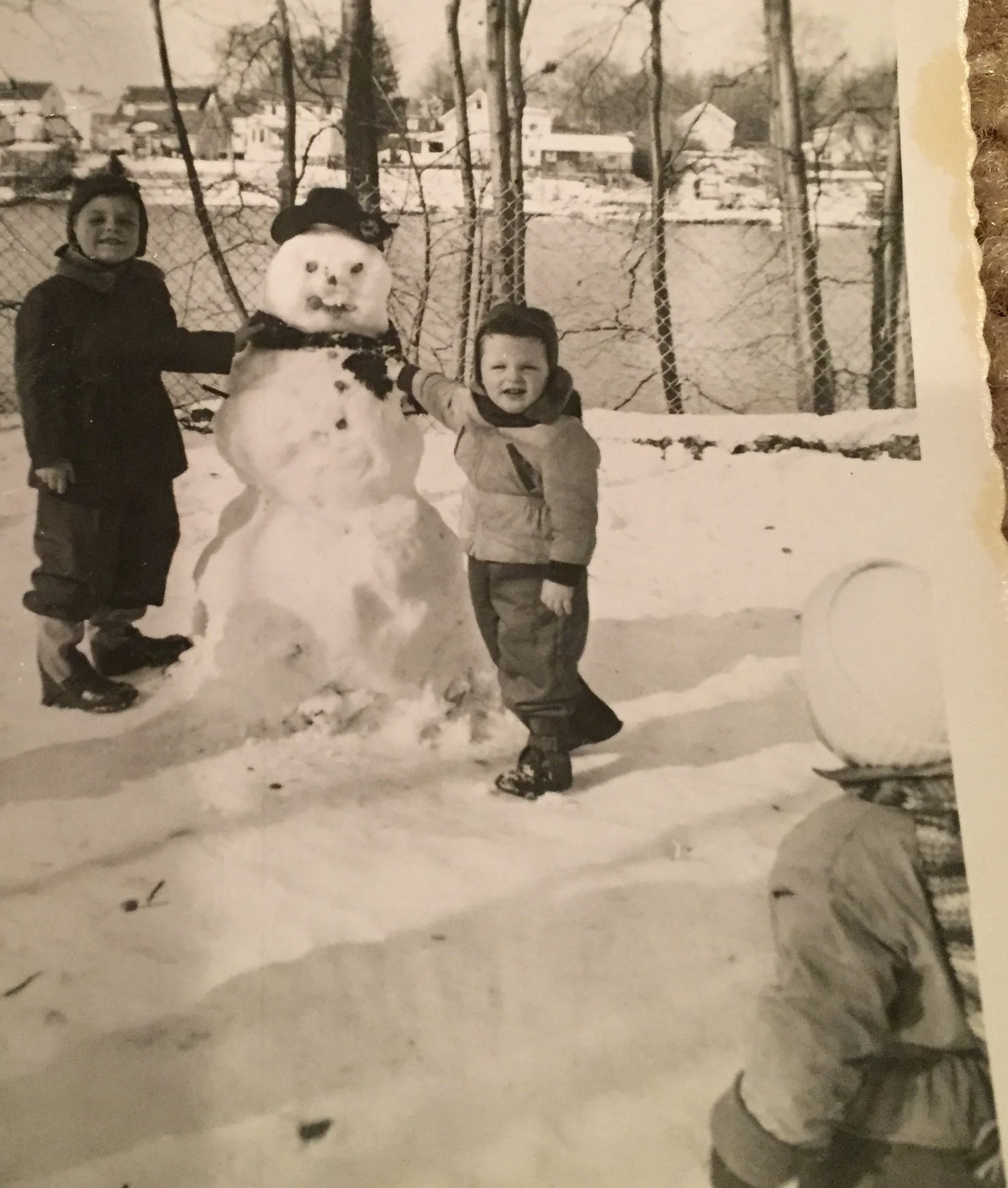

Mianus Village kids, from left to right, Jackie Scully, Dennis Scully, and Eleanor Antes with the Mianus River in background.

On Christmas Eve, we’d come out of candlelight church service and it always seemed to be snowing. I can still hear mother singing “Hark the Herald Angels Sing” as she tiptoed down the church’s steep stairs in black dress boots.

Markie and I, her twin boys, hung on each arm. Our kinky blond hair and red rubbery cheeks might have looked angelic, but our tongues were devilishly uncoiled to catch falling snow flakes. Behind us came father, pulling the collar of his gray overcoat above his ears. He would always be cursing cold nights as he struck match after match trying to light a cigarette.

Old St. Catherine of Siena Church and Rectory, Riverside , CT, about 1955.

Mother would look back and roll her eyes at him just as she came to the verse: “Peace on earth, and mercy mild, God and sinner reconciled!”

Some Christmases stick in my mind more clearly than others. I may have been seven or even ten when father slid on his backside down the slippery stairs of the old St. Catherine’s Church, screaming an obscenity that made people stop and stare. I can never remember the year. But the Christmas I’ll never forget—and has never been topped—happened when I was eight. That was the year of the blizzard of ’55.

It was also the year the Widow Hudson blew herself up.

Snow began falling hard as we walked home from school, two days before Christmas. Fat, wet flakes stuck to us like glue. Us kids were sliding on the sidewalk, beside vehicles crawling along the Post Road. Older boys ran onto the highway, grabbing onto the back fenders of slowly moving cars and gliding on their boots like skis. They called it “boot hitching,” but it was way too scary for us fourth graders.

Instead Bobby and I rolled snowballs until they became hard as rocks in our woolen mittens. Like soldiers on the front line, we knelt behind a rock wall near Mianus Village, waiting for the enemy--mongrel dogs with whip-like tails. In our neighborhood, they were all garbage eaters, bicycle chasers and, worst of all, snarling ankle biters. That made them fair game. But when snow covered the ground, they were also cagey as foxes. They knew it was payback time.

And so we attacked trailer trucks creeping up the Post Road from Cos Cob to Riverside. We’d pump our arms up and down, signaling enemy drivers to blow their air horns. If they did, we let them pass; if not, we attacked.

Before the Connecticut Turnpike opened in 1958, truck traffic traveled on the old Post Road running through the center of Greenwich, CT.

From our rocky ramparts, it was hard to miss those gray, grimy trailers. Winding up like the great Johnny Podres of the Brooklyn Dodgers, who had just beaten the dreaded Yankees twice in the World Series, we threw high, hard fastballs. Snowballs boomed like thunder on side panels before shattering into a million pieces. Just then, a trucker’s brake lights flashed red, as if he were going to pull over and chase us down.

We ran like deer across two backyards, jumped a fence and stopped breathlessly in a lane near the Widow Hudson’s house, a block from home. The widow was in the front yard, raking wet, snowy leaves. We looked up at the falling snow and then down at her rake.

She looked at it too and spoke in what mother called proverbs: “When a task is once begun,” she said serenely, “don’t leave it ‘til it’s done.”

The Widow Hudson was an eccentric old woman who spoke in proverbs.

We shook our heads in agreement and kept moving.

By late afternoon, the gray sky—missing a setting sun—darkened to early night. The temperature dropped like a guillotine and the wind began to howl. Our little house became drafty as a barn. Markie and I walked the hallways with Afghans around our shoulders. We talked about living in igloos until spring and making money shoveling driveways. Outside the white beast raged. Specks of snow swirled around street lamps like a million moths. Everywhere the ivory flakes piled up, five times as high as leaves under an oak tree in October. All night long the storm, now called an old-fashioned “Nor’easter,” roared and roared.

At dawn, we threw off Army blankets, stood up and looked out the window. We were snowbound in a white world, glistening, shining, almost too bright to see without squinting. All day long, the sky brightened and darkened, brightened and darkened. When it turned battleship gray, the wind whistled and snow fell again. Father was jumpy as a rabbit, worried the sagging roof above our porch might collapse. Wearing a red plaid jacket and a floppy felt hat, he climbed high on a painter’s ladder, yellow broom in hand. Our job was to hold the ladder from tipping over. White frost poured from his nostrils just as an avalanche of snow fell down our shivering necks.

Early in the afternoon, we were shoveling the Koerners’ driveway when all of a sudden we heard a blast louder than the fireworks finale on the 4th of July.

“Kaa-boom,” echoed up and down the street.

The concussion knocked us over. Windows rattled in every house.

Stunned, Markie and I looked at one another; our mouths open wide as choirboys. Two houses down, right there on the corner of Lois and Lilac Lanes, the sky was full of orange flames. When it died down, a black, sooty cloud rose above Widow Hudson’s ranch house. We climbed to our feet, just as a sheet of tin roofing fell on the snowy street. Without a word, we ran towards her house. All along the street, doors were opening, dogs barking, people screaming.

In a big snow storm, the Widow Hudson’s house suddenly blew up.

Just then there was a second muffled boom.

We turned the corner and entered a war zone. The roof of the widow’s house was gone, as if pried off by a giant can opener. Her windows were blown out; smoky fires were burning everywhere. And there on a snow bank lay the widow. She was stretched out like a snow angel. Make that a fallen angel in a ragged blue bathrobe with singed gray hair and a cigarette hanging out of her mouth.

Markie jumped onto the snow bank and asked, “You okay?”

She stared at her house for a few moments, looked at her cigarette and answered, “What’s done cannot be undone.”

Right away, old Mister Phelps, in shiny black pants, red suspenders and a holey undershirt came running up to me, hollering that he had seen the whole thing.

“She went flying right outta the house…I’m telling ya’, she went up like a Roman candle.”

I stood still as a statue, looking at him. My eyes open wide as portholes.

“Jezum Crow, Mikey boy, I hain’t never seen nothin’ like it.”

Later, everyone agreed the widow must have been in shock for no person in her correct mind would lie there, as she did, and act so calmly. Mr. Phelps helped her up, just as a police cruiser with snapping tire chains skidded to a stop.

The widow looked at her cigarette again, took one last drag and threw it away.

“Little causes produce great effects,” she declared.

It seems the widow had smelled gas all morning, but her phone line was down and her doors blocked by snowdrifts. So she busied herself wrapping presents for her grandchildren who would visit Christmas morning. A few days later, the fire chief was quoted in the Greenwich Time, saying it was a miracle the widow had not been poisoned by the gas or blown to bits by the explosion. The first blast blew off the roof when she lit her cigarette, knocking her to the floor. Seconds later, the same cigarette ignited a pocket of natural gas beneath her, almost launching the old woman into earth orbit.

That night at seven sharp we were in our pew at a Christmas Eve candlelight service, listening to the bell choir play the “First Noel.” That’s when Markie and were twirling our candles, jabbing wicks at one another when no one was looking. We could barely sit still as we waited for the church lights to be turned off and the congregation to rise with flickering candles and sing “Silent Night.”

Christmas Eve candlelight service with the choir singing the First Noel and Hark The Herald Angels Sing.

After church, our family gathered for a traditional party. Our staircase was draped in garland, waxy bay berries, and tiny white lights. In the corner of the living room a fat balsam sagged under red, green and white bulbs, dozens of shiny ornaments, and pounds of tinsel.

Father’s two laughing brothers soon came through the door, carrying bags of presents in one arm, and shaking hands with the other. Their wives, always wearing itchy woolen sweaters, passed hot plates to mother and hugged us hard enough to break ribs. Then they pulled us under a mistletoe in the hallway and planted red lipstick kisses on our checks.

Pretty soon, father escorted his dead mother’s sister, Aunt Veronica, a black-draped widow, through the doorway. As soon as she spotted us, she bestowed tight-lipped kisses that smelled of port wine.

Mother kept shooing us out of the kitchen as we tried to sneak sweets off the table. When no one was looking, we especially liked to twirl our fingers in a bowl of whipped cream reserved for a cherry pie.

Once Aunt Margaret arrived with her husband, we all moved to a small sunroom where mother kept an untuned piano and her sewing machine. As was our custom, she and Aunt Margaret took turns playing Christmas carols while we sang along. At the end, Aunt Veronica always asked for the same tune. Mother would nod and sing it in a wistful way that always brought tears to the old woman’s eyes:

“…have yourself a merry little Christmas…”

Here we are as in olden days,

happy golden days of yore...

Faithful friends who are dear to us

gather near to us once more…

Through the years we will be together

if the fates allow.

So hang the shining star above the highest bough

and have yourself

a merry little Christmas.

When she finished, the adults clapped hands and hugged one another.

Markie and I run over and kissed mother and Aunt Margaret on the cheeks then grabbed their arms, saying, “Now let’s open them presents.”

Everyone laughed and followed us into the living room. In our family, us boys opened gifts from uncles and aunts on the eve, but Santa Claus presents were saved for Christmas morning. Within minutes, the floor was piled high with crinkled wrapping paper and silver bows as we politely said “thank you” for yet another awful—to our way of thinking—present. That year we got yellow rubber mittens, green sweaters with leather elbow patches, tan cowboy pajamas, and the one that almost made us throw-up: red and black plaid bow ties.

At 10 o’clock, we said goodnight and went to bed. We never slept on Christmas Eve. For two hours, we whispered and giggled in happy anticipation of what was to come.

Every once in a while, father would walk down the hall and announce: “Settle down now OR … (obviously searching for the right words) there will be no Christmas.”

We’d look at one another, stifle laughter, then lower our voices for a few minutes.

By midnight, Markie was breathing heavily but I was still awake. The voices in the living room became fainter and fainter. At last they softened to gently flowing streams and waves lapping distant shores. I tried to say the words of “Silent Night,” but somewhere between ‘all is calm’ and ‘all is bright’, I too fell asleep.

We awoke at sunrise with bright smiling faces. That morning, we got a Red Ryder sled, Lincoln logs, tinker toys, Chinese checkers, hockey skates and paint-by-number sets.

By nine o’clock, we were outside, giving one another rides up and down the snowy street. Smoke curled upward from chimneys. Pretty soon, we met Maureen Wolfe’'s father, beaming broadly. He was walking a black terrier puppy dressed in a red and white striped vest.

“That’s one for the record books, boys,” Mr. Wolfe said pointing to the ruins of the widow’s place, as he tugged the dog’s leash.

We sat down on the sled and stared at it. The little house and everything in it was either charred or gone. Her trees were draped in frost and dripping water from the fire hoses. Mr. Fox said he and his wife had visited the widow at Greenwich Hospital on Christmas Eve.

The widow didn’t seem to care about her house, he told us.

She had just said, “The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh.”

We nodded seriously and looked up from the sled as a ghost car crunched its way up the street. Someone waved and then it disappeared. Even now, its headlights glow in my mind, as do memories of that long gone Christmas in our once little town of Greenwich.

-END-

Copyright 2022 by Jack T. Scully