Poetry Excerpts from Mianus Village

Deep in our subconscious... lie all our memories…

Forgotten debris of forgotten years

Waiting to be recalled…

Waiting for some small, intimate reminder…

An echo from the past…

-- Noel Coward, Nothing Is Lost.

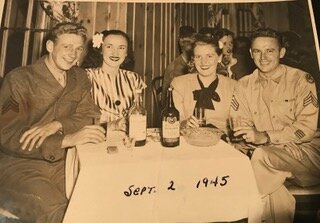

Coming Home

World War II quit

just in time

for daddy. After

fighting its way

up the boot of Italy,

his regiment boarded

a liberty ship in Genoa

bound for Japan.

He was lying

in a hammock smoking

a Camel and feeling

doomed

when the news

crackled through

the James Longstreet’s intercom—

the Japanese had

surrendered. His ship dropped

anchor just east

of Panama Canal

and everyone cut loose

drinking rubbing alcohol cut

with pineapple juice—

“to keep ya from

goin’ blind.” Eight days later,

he skipped

down the gangplank

at the Brooklyn Marine Terminal,

got paid, discharged,

and that night,

believing his luck

had finally changed,

blew $20

for a taxi ride

to Greenwich—

an extravagance my mother

never let him forget. Right away

he moved in

with the in–laws

and became obsessed

with buying a Studebaker,

finding a job and starting

a family—though

not always

in that order.

Mianus Village

A gold coast

hanging on the bank

of a tinsel-glistening river

but nobody knew that in 1946

when the VA

bought the land cheap,

bulldozed a strip through

the green woods,

built 40 matchbox houses

—750 square feet each—

and rented them

to WWII veterans

who couldn’t otherwise

afford a place

in the sun.

Daddy qualified

when he got laid-off

at the nail factory

and we arrived

at this launching pad

of our lives

when I turned two.

That spring mother planted

a bed of purple iris—

whose iridescent petals

brightened our days

and the kitchen table

every summer

of my boyhood.

Within a week,

Daddy cut a gate

in the chain link fence

with pointy tips,

built by the government

to save us

from drowning ourselves.

Nobody died

but Jeffrey Bell

once got seven stitches

in his throat

after bayoneting himself

on a razor-sharp prong—

a foolish

thing for sure

because two black labs

had already dug

a trench beneath

the lower rail

deep enough

for a teenybopper

to do the limbo.

War Brides

Toward the back

of the village,

six wives

lived like sisters

in the springtime

of their lives,

sharing groceries,

Patti Page records

and occasional heartaches.

I can still hear them

reading Dr. Spock aloud,

fretting about polio,

and laughing at Lucille Ball.

In the early 50s,

they stayed home

raising babies,

gathering weekly

for coffee and

their favorite morning show—

Arthur Godfrey Time.

I was shy as a boy

and stuttered

so I liked to sit

quiet as a cat,

my eyes and ears—antennas

of surprise and wonder—

uploading everyday talk

and stories of the big war,

which still brought laughter

and tears to people’s faces.

This one morning

I watched them

squeeze their butts

onto our swayback couch

in front of the TV set,

fanning themselves

with Life magazines

when that Italian heartthrob,

Julius LaRosa,

sang his number one hit,

“Eh Compari.”

When they left, I went

from saucer to saucer

sipping dripped coffee

then sat on the front step,

my heart buzzing

like a bee in a bottle.

Back then,

the world beyond the village

was vague as fog,

that is until the harsh realities

of life showed up.

First, Laura Barnet

died young

of cancer, then Molly Plant

ran away with an

old boyfriend, and one-by-one,

mother’s other girlfriends

began moving

to bigger houses

in better neighborhoods.

She never connected

with the second wave of families

moving into the village

and as the years passed

some people thought her

stuck up. All I saw

was this lioness’ hunger

for her cubs,

not wanting us

to end up poor

like her and daddy,

wearing Thrift Store clothes,

driving beaters,

and whittling our bones away

working for people

with blue blood

in their veins.